The Natural Process (Coffee Processing, Explained)

Coffee processing is one of the most decisive factors in how a coffee tastes. Origin tells part of the story — but processing often determines how that story shows up in the cup.

In this guide, we’ll break down the natural process: what it is, why it tastes the way it does, and how to brew naturals so they shine without becoming overwhelming.

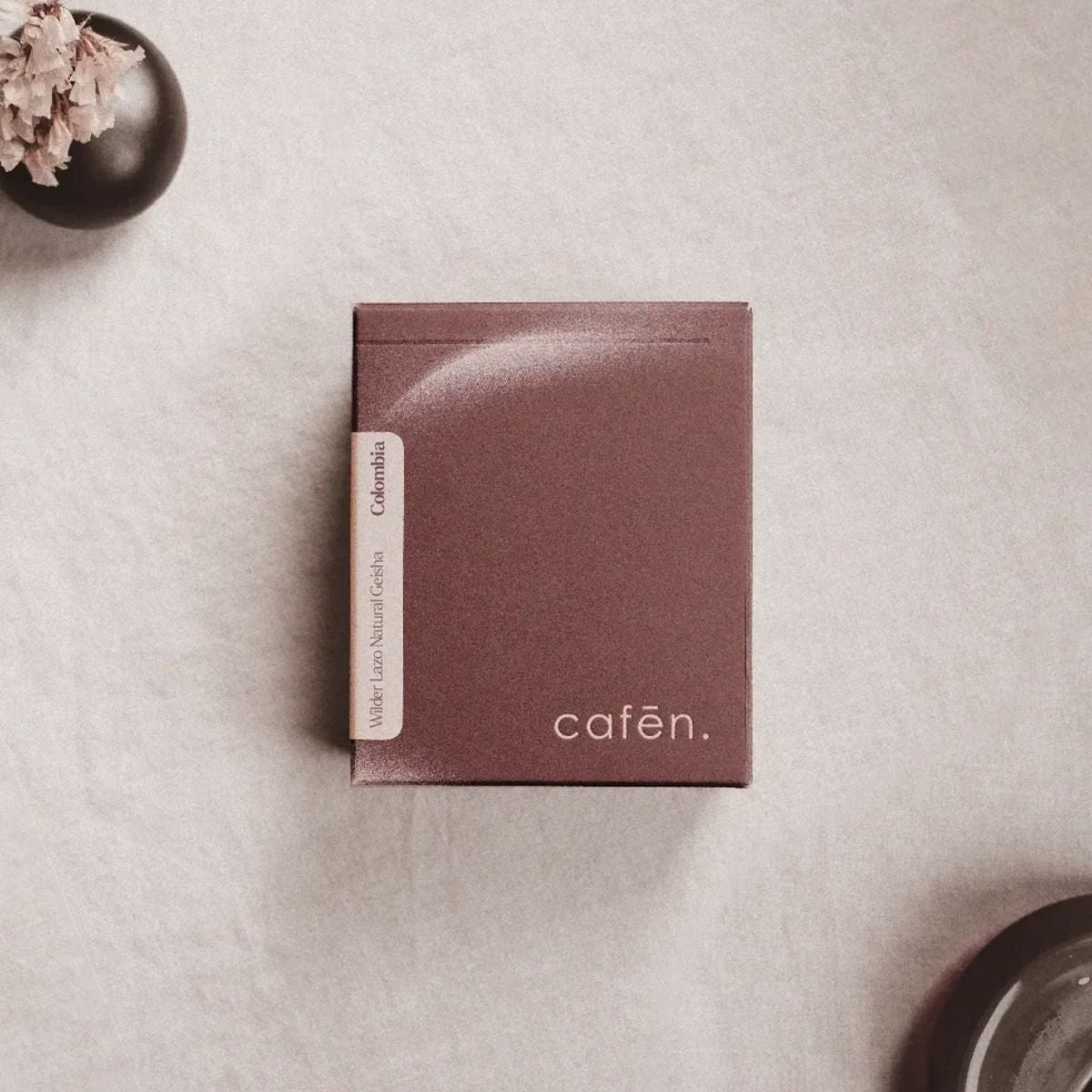

Naturals are often the coffees that make people stop mid-sip and go: “Wait… coffee can taste like this?” Big fruit, huge aroma, dense sweetness — and when done right, surprisingly clean.

So, what exactly is the natural process?

In natural processing, the coffee cherry is dried fully intact — seed inside the fruit — typically on patios or raised beds. Depending on climate and technique, drying can take up to two to four weeks.

For higher quality naturals, there’s usually a careful sorting stage before drying to remove underripe, overripe, and damaged cherries. This is crucial: fermentation can’t “fix” poor raw material — it only amplifies what’s already there.

As the cherries dry, their bright red color gradually darkens into deep purple or brown. Once fully dried, the hardened fruit is mechanically removed, and the coffee is stored in parchment to rest before export.

Patio-dried vs raised-bed naturals

Not all naturals are dried the same way. The drying environment has a major impact on consistency, cleanliness, and how intense the fermentation character becomes.

Patio drying

- Coffee dries on concrete or stone patios with high thermal mass

- Often dries faster due to heat retention

- Can lean toward riper, heavier, sometimes more rustic profiles

- Requires frequent turning to avoid uneven drying

Raised-bed drying

- Coffee dries on mesh beds elevated above the ground

- Airflow from above and below enables slower, more even drying

- Typically results in cleaner aromatics and better control

- Often used for higher-quality lots

How does the natural process affect your cup?

Once cherries are placed on drying patios or raised beds, naturally occurring yeasts and bacteria begin feeding on the sugars inside the fruit. This triggers fermentation — not in a tank, but inside the cherry during drying.

When well controlled, this stage can turn your cup into a tropical fruit bomb: intense aroma, high sweetness, and a dense, juicy mouthfeel.

If fermentation isn’t properly controlled, the cup can drift toward kombucha-like acidity, boozy notes, or even vinegar-like sharpness. Control is everything — moisture, sunlight exposure, airflow, turning frequency, and drying time all play a huge role.

Just by smelling a great natural, you’ll often get hit by an intense fruity aroma — jammy, tropical, or winey — before you even brew it.

Final thoughts

Natural processing highlights the relationship between fermentation and drying more clearly than most other methods. Because the fruit remains intact, the producer’s decisions directly shape the final flavour profile. When those decisions are well executed, the result can be a coffee that is both vibrant and clean, with layered sweetness and a distinct sense of origin.

How to brew natural coffees

Because natural coffees ferment inside the cherry, the beans tend to be slightly softer than the same coffee processed as washed. In practice, this means grinding a natural often produces fewer fines.

Fewer fines means less natural resistance in the coffee bed — which is why naturals often benefit from a slightly finer grind, simply to prevent the water from running through the brew too quickly.

Keep this in mind when brewing naturals:

- Even with a finer grind, expect a slightly faster brew time than a washed coffee. Naturals generally extract more easily.

- Naturals often taste cleaner and juicier at lower brew temperatures, typically around 88–92°C.

- They tend to be more forgiving to brew at home, even if your water or equipment isn’t perfectly dialled in.

- While naturals usually prefer a finer grind, very dense coffees — especially Ethiopian and Colombian lots — may still require a coarser grind than expected. Density matters as much as processing.

- For pour-over, we often prefer using the SIBARIST B3 filters , as they help emphasise a thicker, sweeter, and more syrupy mouthfeel — a great match for the character of natural coffees.